Coral Reef Food Web

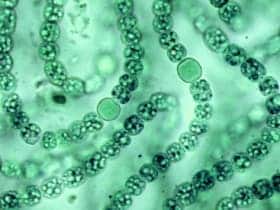

The coral reef food web – like those of all highly diverse biological communities – is exceedingly complex.

Hence, attempting to describe all of the myriad linkages in any coral reef food web is well beyond the scope of this website (or of current science).

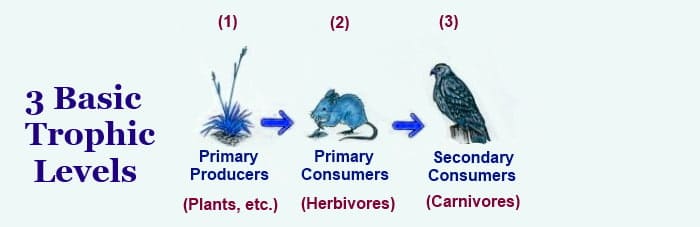

Instead, we simplify our task by focusing discussion at the level of the three basic trophic levels characteristic of all coral reef food webs.

This approach reduces the complexities of feeding relationships in coral reef communities to a far more manageable level.