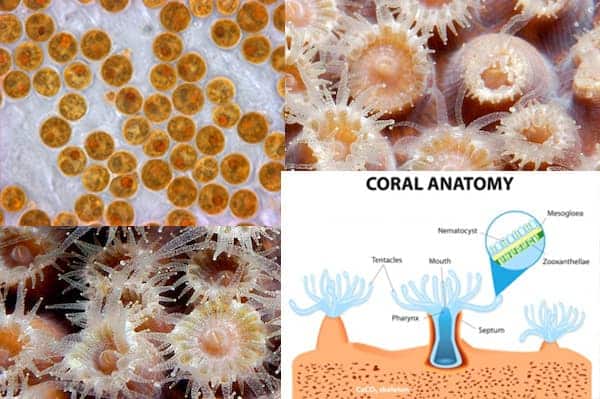

However, some species form colonies that do not readily fit into any of these general “shapes”. Although many species may usually be readily recognized by the characteristic appearance of the colony, identification in some cases requires close and careful scrutiny of the form and pattern of the individual polyps that make up the colony’s surface.

Coralline Algae

A key part of answering the question “how are coral reefs formed?” lies in the fact that growing upon and amidst the coral colonies are an unusual group of plants, called coralline or calcareous algae. These coral reef plants, like the hard corals themselves, also incorporate calcium carbonate into their bodies, thereby a pivotal role in helping to build and cement the reef into a cohesive structure.

Other Contributors

Another quite different type of coral (Millepora spp., commonly known as fire coral, also contributes to the framework of many shallow reefs of both the Indo-Pacific and Greater Caribbean regions.

Upon the solid structural foundation built mainly by hard corals and calcareous algae grows a superficial layer of sponges, octocorals, and numerous smaller less conspicuous kinds of animals and plants that together provide additional dimensions of structural and biological complexity and diversity to coral reefs.

So, to answer the basic question “how are coral reefs formed?”, we must consider not only the growth of hard coral colonies, but the contributions of a host of different types of marine life as well as dynamic forces of the ocean and the earth itself.

Our section on “Additional Resources” can provide more information related to the question, “how are coral reefs formed?”